1861: A New Era

ACT I: The Eras of Invention, Production and Distribution

Introduction

Throughout history, the need to communicate has been a constant. Fire and smoke signals eventually gave way to carrier pigeons and messengers on horseback. But it was a major leap in 19th-century technology that put an end to these primitive predecessors of modern-day communication.

In 1861, telegraph wires stretched from coast to coast, revolutionizing the way people communicated. Experts like Elisha Gray and Enos Barton were at the forefront of this rapidly expanding technology. In May 1869, they joined forces, and a small telegraph company called Gray & Barton was founded.

The partnership between professor-inventor Gray and manufacturer-businessman Barton was a solid match. Gray & Barton started as a small electrical shop focused on telegraph keys, as well as fire alarms and hotel “annunciators” (basic switches allowing guests to ring the front desk from many stories above)—practical products for newly electrified city living.

Opportunity is Calling

Gray & Barton did well. It bought several small electrical companies, merged with Western Union in 1872 and was renamed the Western Electric Manufacturing Company. Around this time, Gray was experimenting with different innovations, including “voice telegraphy”—transmitting vocal tones by wire instead of dots and dashes. Basically, he was inventing the telephone. He even filed a “caveat” (a kind of provisional patent) for his passion project.

But Western Union and most other telegraph industry experts saw the “talking telegraph” as a mere novelty, a toy, a waste of time. Gray’s associates, including Barton, were much more interested in figuring out how to get multiple telegraph signals transmitted on a single wire. They even offered a $1 million prize for the first inventor to crack this code. So Gray shelved his work on the telephone and focused on multiple telegraphy.

We all know what happened next. Two revolutionary inventions—the telephone in 1876 and the lightbulb in 1879—changed everything. Despite a long court battle over the telephone patent, Gray lost—missed the call, you might say—but his company still found a way to adapt and benefit from the evolving technology. In 1881, when American Bell Telephone Company needed to mass-produce telephone equipment for a market set to explode, it turned to Western Electric. The company soon became the world’s largest manufacturer of telephone receivers, transmitters and induction coils.

A Lightbulb Moment

In 1882, Thomas Edison opened the world’s first commercial power station in Lower Manhattan. Little by little, America brought electricity into its homes and businesses, and in 1910 the national standard for residential electric current was set. Now, mass production and distribution of electricity was finally possible.

Western Electric came through with exciting products for a newly lit world: arc lights, wires, batteries, fans, motors, and “practically every electrical item used by electrical contractors, power and light companies, and general industry, from soldering paste to telephone poles.”

As the country became electrified, the company expanded into small appliances that made life easier for countless Americans, including sewing machines, vacuum cleaners, personal fans, clothing irons and even the Graybar Stimulator, that ridiculous “body-toning” contraption with a belt strapped to an electric motor that you always see in old film footage.

Western Electric spun off its supply department in 1925 and named it Graybar Electric Company in honor of its founders, Gray and Barton. Graybar became a major distributor of the radio transmitters and receivers that brought mass entertainment into homes of Americans. It was a good time to catch the perfect wave of a new industry.

But it was a nationwide wipeout that caused Graybar’s next transformation.

Mass Distribution

When the Great Depression hit, priorities shifted for both consumers and purveyors of electrical products. For Graybar, “the growth from invention to production to mass production has naturally ended in mass distribution,” according to the company’s 70th anniversary history booklet. Of course, this was hardly the end of the line.

Graybar’s “era of mass distribution” continued through World War II and afterward, through the social and political changes of the 1960s, and through the energy crises of the 1970s. The early 1980s brought a period of telephone industry changes, and a new opportunity for Graybar to reinvent itself.

Under a new President, Jim Hoagland, Graybar moved from New York City to St. Louis in 1982. “We wanted to be in the Central Time Zone,” Hoagland said, “because it’s easier to manage a nationwide business from a central geographic location. Second, we wanted to find a place where our employees could have a reasonable commute, buy a house at a reasonable price and send their kids to good public schools.” The move coincided with a decision to discontinue Graybar’s household appliances division, another major shift for a company that was once literally a household name.

But it was industry deregulation that created the bigger transformation in Graybar’s business. After the 1984 antitrust case that effectively split AT&T’s regional companies into the “Baby Bells,” Graybar re-established its partnership with the company once known as American Bell, revitalizing its communications business. Telecom and data products grew from 10 percent of Graybar’s business in 1980 to 34 percent in 2000.[ With fiber optics and network products becoming a staple of Graybar’s distribution business, it was time to bring digital technology in house and revamp the company from the inside out.

Act II: Our Digital Transformation

Graybar Goes Online

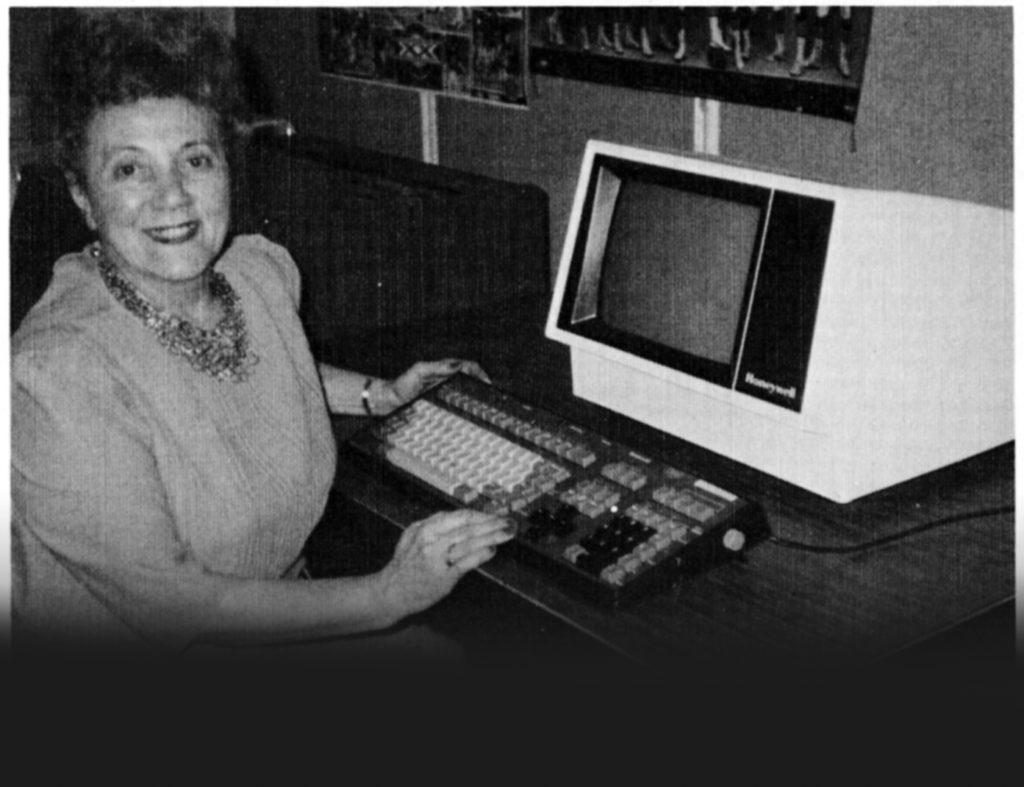

Well before the internet reshaped our lives, Graybar was experimenting with online ordering via computer-to-computer communications over telephone lines. In managing the warehouse logistics for one of the Baby Bells, Graybar developed an early electronic data interchange (EDI) protocol for paperless ordering, shipping and invoicing. The company started working with Honeywell Bull in 1987 to establish its first mainframe computer system. This made Graybar one of the first national distributors “to connect our entire organization and have a national inventory database,” said Graybar CEO Kathy Mazzarella, who started at the company as a customer service representative at age 19. “That changed the dynamic completely.”

In 1995, Graybar launched its first website. The company transitioned from a dial-up distance learning system to its first web-based employee training platform in 1997. This platform, called Virtual Campus, offered more than 300 courses and curricula tailored to specific jobs.

The Eye of the Storm

As the company grew rapidly through the late 1990s, technology-enabled services such as barcoding and vendor-managed inventories became increasingly important to Graybar’s business. This growth set the stage for the big shift in the early 2000s, when the company made a $100 million investment to implement its SAP enterprise resource planning platform.

Right about then, with a huge investment on the line, the dot-com bubble burst.

Tech customers folded, revenue plummeted, cost reductions were necessary and then, President Carl Hall was diagnosed with a terminal illness. “It seemed that everything that could go wrong did go wrong,” Mazzarella said.

Incoming President Bob Reynolds “was the right leader to have at the time” and saw the SAP conversion through. With SAP, Graybar replaced its aging, high-maintenance mainframe, which improved management of physical inventory, enhanced financial reporting and gave the company greater insight into the supply chain.

The learning curve was steep and long, but the investment paid off. In 2006, Graybar saw a 16.8 percent increase in revenue and an 88 percent increase in income from operations. The SAP platform also provided a foundation for further technology innovation. For example, Graybar implemented Delivery Advantage, a mobile tracking solution that captured data from its delivery drivers including location and estimated time of arrival as well as photo proof of delivery. The innovation won Graybar a prestigious “20 Great Ideas” award from InformationWeek magazine in 2007.

Meanwhile, a relaunch of Graybar.com made it easier for customers to check pricing and availability, and place and track orders. The new site also included major self-service features, allowing “users to manage their business with the distributor according to their own preferences and schedule.”

All this excitement, just in time for the economy to crumble again.

The global financial crisis hit all industries hard but was especially tough on construction, which had been a pillar of Graybar’s business since the 1970s. Graybar saw a steep decline in revenues in 2009 and 2010 as customers delayed or halted new construction or renovation projects. Meanwhile, the competitive landscape started to shift, as big-box stores and web-based retailers began to expand into the wholesale business. Graybar’s financial position remained strong and the company weathered the downturn, but the industry was changing like never before.

Graybar had all the right pieces in place. Could the company compete in this new era?

ACT III: Powering the New Era

Invention and Reinvention

Then and now, our business has always been about communication and light, connection and power. Since 1869, Graybar has survived and thrived by switching gears, evolving time and again, era after era. It’s now a great time to reimagine one more time.

It’s also a great time to remember the choice our founders had, between improving the efficiency of the telegraph and completely disrupting the industry with new innovation. On one level, it makes good business sense to focus on the basics of running the business—making it more efficient, productive, profitable, improving margins and market share. That’s what Western Union was trying to do when it wanted to figure out how to send multiple signals simultaneously over a single wire.

The experts knew their industry well and were laser-focused on advancing familiar technology. They’d forgotten that the point of the telegraph wasn’t to send as many telegraph messages as possible over a single wire. The point was communication. And Bell beat them to the next punch.

It makes equally good business sense to focus on transforming the business. For Graybar, powering the new era is no longer just about fulfilling customer orders efficiently, but rather, helping customers bring buildings to life with innovative products, distinctive services, and transformation of the supply chain. Instead of focusing on the products that have been our bread and butter for many years, we can explore new ways to bring about something truly transformative.

From Distribution to Solutions

Perhaps the answer lies in changing how Graybar thinks of itself. “Maybe we should not think of ourselves as distributors anymore, since what we really are is a service organization, providing services to our manufacturers and to our customers,” Mazzarella said. “Every single customer requires a different type of solution or service. . . . It’s about redefining the role of distribution in the supply chain and transforming the expectation, so we become what we need to be to remain relevant between the suppliers and our customers.”

Understanding and adapting to our customers’ needs is mission critical. We can deploy e-commerce and other digital platforms to support those changing needs, but what truly sets Graybar apart is our people. The highly experienced employee base is what differentiates us from e-commerce-only competitors, and our slate of value-add services—just-in-time (JIT) delivery, material kitting and SmartStock Inventory Management—represents a marriage of tech and human capital that serves our industry better than a website ever could.

“What we need to do is create an environment where a customer can choose how they do business with us,” said Mazzarella. “If they prefer working with human being, they can. If they never want to talk to a person and primarily use technology, that’s fine, too. . . . Digital transformation doesn’t mean we replace all people. Digital transformation is about using technology to help people recognize their full potential and develop their skills.”

While holding on to the personal touch that makes us who we are, our next challenge is about once again transforming Graybar: this time, from a distribution company to a tech company, and shifting our focus from distributing products to providing consultative support and accelerating innovation in the industry we’ve known for 150 years.

Change is in our DNA,

whether we’re responding to the times or leading that transformation, powering the

industry into a new era.