Agility and Adaptability

ACT I: Reigniting the fire of Graybar’s rich history of innovation

Introduction

If a quarterback throws a series of successful passes to one receiver, chances are the defense is going to change their strategy to cover that receiver. So the quarterback has to make a change, too.

The challenge? Shake things up and use the situation to the team’s advantage.

Companies face that same kind of challenge. Change happens quickly and often, whether it’s on a football field or in the distribution business.

Graybar CEO Kathy Mazzarella likens Graybar to “an organic entity that needs to live, and needs to grow, and needs to spread, and needs to continue to recognize its potential. We do evolve, we’re agile, and we move, similar to a human being.”

Adapting to the new, collaborating and learning from each other, and having the agility to pivot, cut and change course faster than a star quarterback are necessary qualifications in the breakneck pace of business today. It’s not always easy, especially for a company that has a long track record of success and for people who are great at what they do. But it is necessary.

A change in thinking

“Graybar is going through some growing pains,” said Beverly Propst, Senior Vice President, Human Resources. “That’s not a negative thing, but it can cause tension. That’s one of the challenges we have to break down right now.”

“Everybody is just trying to do a really good job. And there’s nothing instinctively wrong with that,” she added “But having that mentality of doing the best work they possibly can tends to give people a limited scope of visibility.”

Working in a proverbial bubble can prevent Graybar employees from recognizing that what they’re doing has an impact on many people. Gathering input reduces frustration and helps ensure new ways of doing business will be accepted and even welcomed. Learning to cooperate effectively allows a company to adapt to minor modifications and even total transformations of the way things have always been done.

Sharing skills and relying on the strengths of others have been hallmarks of Graybar since the beginning. So have change and the ability to adapt to what’s new and different. It wasn’t ever easy. But even in its earliest days, the company realized it couldn’t sit still if it was going to compete in a world that was moving fast—even in the 19th century.

We’ve been here before

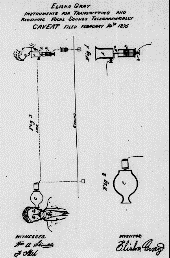

Graybar founders Elisha Gray and Enos Barton knew how to make the best use of their individual skill sets and how best to meld those talents together. Gray was the creative guy, the inventor, the one who liked to tinker. He held more than 50 patents.

Barton was a telegrapher and businessman. An early employee described him as “unassuming, quiet, with an almost uncanny grasp of business problems and an ability to analyze them.”

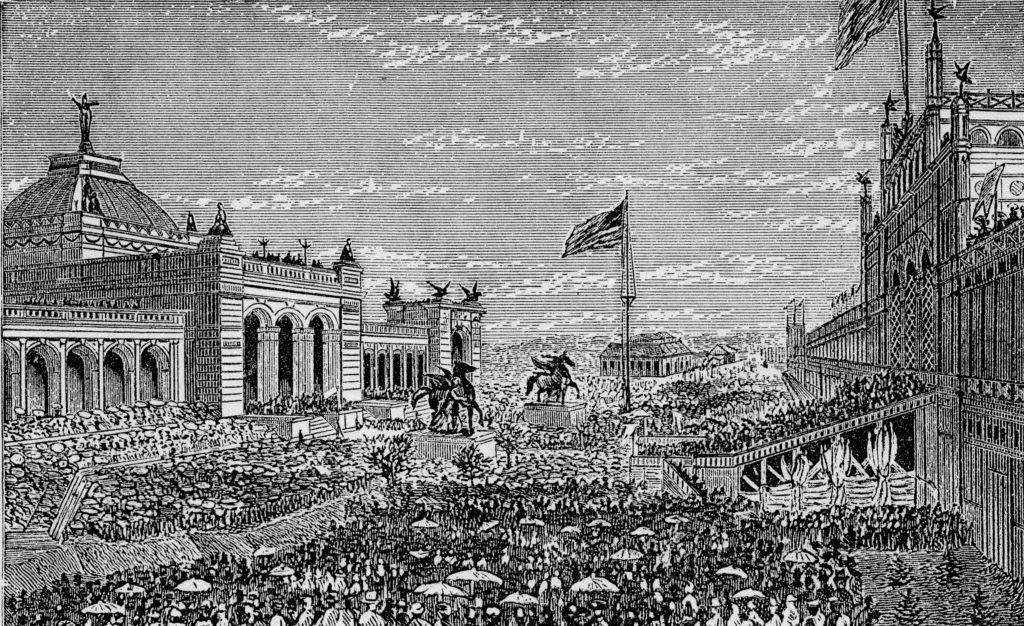

While initially specializing in making telegraph instruments, burglar alarms and other electrical devices, the founders were alert to opportunities in other fields. Barton had an eye for technology and was willing to take a chance on new ideas. Western Union was willing to pay up to $1 million to the inventor who could make their wires carry a number of messages simultaneously. Gray took on the challenge, and “astonished the judges” of the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 by sending eight telegraph messages at once.

It was an accomplishment that wouldn’t mean much just a few years later, but the company kept plugging ahead.

ACT II: It pays to know both sides

Moving on without delay

Gray and Barton knew that even the best laid plans sometimes go awry. And that when they do, you can either give up or be agile enough to take advantage of the unexpected.

Case in point: Officially, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. But Elisha Gray submitted an application to the U.S. Patent Office the same day that Bell did. Some believe that Bell got special treatment, especially since the applications (and plans) were virtually identical. (Even the author of The Telephone Gambit: Chasing Alexander Graham Bell’s Secret claims the famous inventor “was plagued by a secret: he stole the key idea behind the invention of the telephone.”)

Quickly rebounding, the company began making phones for Western Union, a Bell competitor. Bell sued, claiming patent infringement. In a shrewd business move, Western Electric struck a deal. By 1881, the company had an exclusive contract to manufacture Bell telephones in the United States.

Adding and subtracting to get the right mix

Transformers, fans and motors were next, followed by a totally new business for Western Electric: the supply department. The supply department promised to stock “all electrical supplies for which there is a demand.” Dozens of well-known suppliers signed on, giving wholesale customers a choice and access to a wide array of products.

The supply department was eventually spun off as a separate company, which became known as Graybar. In the 1920s, Graybar was big in the consumer products world, and the new company’s first president, Albert Salt, wanted to make sure everybody knew the Graybar name. His innovative marketing ideas included spending $1 million on ads and radio spots, publicity stunts such as kissing and joke-telling contests, and, in his biggest coup, getting naming rights to what was then the largest office building in New York City.

It was an exciting period of growth for the electrical equipment industry as the economy expanded and dozens of new electrical devices—including car radios, traffic lights, electric shavers, loudspeakers and motion picture sound systems—made their debut. Everyone was eager to handle all the new products. The company was adapting rapidly to the new heights of industry growth.

The Great Depression put a stop to that. Graybar got out of the branded home appliance business. During World War II, Graybar President Alfred Nicoll wrote: “Our business changed rapidly until our activities were almost entirely devoted to furnishing material and equipment either directly or indirectly for the government to use in its war effort.”

The postwar boom brought the transistor, television, and consumer goods every household had to have.

“That pace of change was fairly easy to handle,” said Beverly Propst. “The learning curve wasn’t as steep, or as fast.” Technology moved at a slower speed and people had time to adjust to change.

Shifting gears mentally

In the 1970s, Graybar began to explore new opportunities with the emerging interconnect industry and took advantage of rapid growth in the construction industry. Salespeople quickly learned that selling to certain customers, such as smaller contractors, was substantially different than selling to large industrial and government customers. As Graybar’s customer base became more diverse, it became clear that a “one-size-fits-all” mindset would no longer work.

Fresh approaches were needed to grow the business. Old ways gave way to new. In 1969, a five-year plan was launched to increase revenues by not only understanding the customers’ needs but also training employees more thoroughly, opening more branches, and upgrading the company’s sales literature and directing marketing.

The Chicago district tried a different approach. It rearranged itself into four market-based departments to deal with customers more directly. By 1972, the approach was adopted companywide.

During that time, and into the 1980s, district and branch managers were kings of their castles, running their operations with little involvement from corporate headquarters. If you were making money, you were left alone.

That was about to change.

Shifting gears electronically

Computers accelerated the rate of change. They allowed Graybar to operate warehouses more efficiently and provide supply chain management services to other companies.

The 1990s brought the Internet, ever-accelerating connection speeds, a growing number of gadgets, and voice, data and video capabilities. As agility became the watchword for businesses, Graybar launched pilot programs for bar coding, paperless warehousing, vendor-managed inventories, and specialized inventory deployment.

Zone warehouses represented a first step toward centralized inventory purchases. Distribution center leaders had to adapt to the new system that replaced their former autonomy.

Between 2002 and 2004, the company spent $100 million upgrading its enterprise computer systems. Spending the money was the easy part. The difficulty was in adjusting Graybar’s business processes to conform to the new software and teaching employees how to use it.

Up until then, change was more gradual. “But when we made a change like putting in an enterprise system, it was overwhelming. Some people even left the company,” Propst said.

In today’s Graybar, though, “that pace of change has quickened. Every month we’re coming out with something new for employees.”

And now: digital transformation

On October 6, 1927, actor Al Jolson said on camera, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet,” and changed the movie industry forever. The same thing could be said about Graybar’s business today.

“Recognizing the disruptive power of technology and using it to our advantage is the first step toward transforming our company to succeed in a digital world,” said Kathy Mazzarella. “However, technology on its own cannot power innovation. True, lasting transformation of our business requires a companywide commitment to think and work differently. We must shift from a mindset of assuming we know the answers based on our past experience to one of continual learning, in which we focus on asking the right questions and seeking out data to guide our actions.”

The digital transformation is exciting to many at Graybar. “A lot of our employees are excited when we upgrade technology,” said Beverly Propst. “It enhances their jobs and improves their ability to do great work.”

Outside influences

Changes at Graybar are only part of the equation. Within the construction industry, the shortage of skilled labor is an increasing concern among electrical contractors.

“If our customers do not have employees and strong labor forces, then we don’t have business, because our customers aren’t growing, said Mazzarella.”

To address this issue, Graybar works hard to promote careers in the electrical industry. And as a supply chain provider, it constantly seeks to create innovative labor-saving solutions that help boost efficiency, safety and productivity for electricians on the job site.

It’s all about building on our strengths and investing in innovation that solves real problems for our customers.

ACT III: Unify by understanding each other

Talk to me

Now more than ever, change is an integral part of the company culture. Innovation from every quarter is encouraging, exciting and enlightening. But in the midst of constant change, it can be challenging to find unity and a shared purpose.

At Graybar, the era of digital transformation is all about using technology to help people achieve more. Customers remain at the center of Graybar’s innovation efforts, and the company is working to inspire fresh thinking among its employees, while improving its speed and agility in getting important things done.

In 2017, Graybar launched an innovation lab at the University of Illinois, and in 2018 introduced an employee innovation program. This program encourages employees to share suggestions to help customers. Quarterly innovation challenges will harken back to the days of Elisha and Enos, when innovation was king. All ideas will go to a central innovation platform, where they’ll be reviewed and funneled to the appropriate areas of the company.

The field is wide open on ideas. They could be enhancements to an existing product or a procedure. Or they could be wholesale changes to workflow, responding to customer needs, creating new services—anything is fair game.

For Graybar’s innovation culture to thrive, the company must also be able to implement new ideas. Graybar’s Enterprise Project Management Organization (EPMO) has created a cross-functional approach to executing the company’s most strategic priorities, a major departure from the silo mentality of the past.

Unofficially, Graybar has been courting this kind of innovation for years. But with a focus on creating a culture of innovation, we’ll have a system in place to discover new ideas and use them to serve our customers and grow our business.

The ability to change has been an important ingredient in Graybar’s success. That’s not going to change. Those who came before us at Graybar knew the value of internal rivalries and outside challenges. Today, that attitude is more important than ever in providing better value to our customers. Together, we can turn our tradition of agility and adaptability into a greater competitive advantage.